THE AESTHETICS OF CAMERA MOVEMENT (2006)

In theatre, the action is aimed at the audience. In cinema, the audience is aimed at the action. Ron Bunzl

INTRODUCTION

Theatre has experimented with moving sets, but until the invention of cinema, it was problematic to portray the commonplace experience of a moving perspective in a changing world. The ability to pick up a camera and move it through space is a challenging freedom. We move the camera constantly: to follow the action to a new location; to create a shifting perspective; or literally, to induce movement into a scene. Camera movement is unquestionably one of the great storytelling devices available to us.

There are moments that are unimaginable without camera movement playing a leading role—such as the opening sequence of Touch of Evil (Orson Welles 1958). Yet much camera movement is meaningless, as in the opening sequence of Sudden Death (Peter Hyams 1995). We get the impression that both directors strive with the same intent: to create a beautiful master-shot that sets the scene for the coming action. Although the Sudden Death opening seems to include all the right elements, it completely fails to entice, whereas Touch of Evil brings us to the edges of our seats.

Camera movement is not essential for narrative development, and in some cases it is superfluous. In Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu 1953) the camera placements are simple and static, yet powerful. In Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (Kenneth Branagh 1994), the rationale behind the camera movement is difficult to imagine, unless the intention is to show the magnificent set.

In these clips, the difference between what works in advancing the narrative and what doesn't is clear. In Touch of Evil, camera movement has a meaning. In Sudden Death, the camera wanders like a child's balloon. In Tokyo Story, movement is simply unnecessary. In Frankenstein, movement becomes a protagonist, but the whirligig perspective of the circling camera has no narrative significance. Who or what is watching? What does it have to do with us, the viewers? Camera movement without justifiable intent is simply distracting.

It's trivial to compare such sequences as these. What is harder, is to compare sequences that are similar to each other in style, form, and quality, and then to attempt to guess why one works better than the other. In comparing like with like, I want to touch on subtleties of camera movement that affect different people in different ways; but first, let’s explore what it means to move 'the moving camera.'

THE STILL IMAGE

The now has a duration. One end is joined to the past, the other to the future, and the now of photography is one single frame. Every image tells a story, or rather, invites you to explore the story captured within one moment. From the context of one frame, we deduce what happened just before, and we infer what will happen just after.

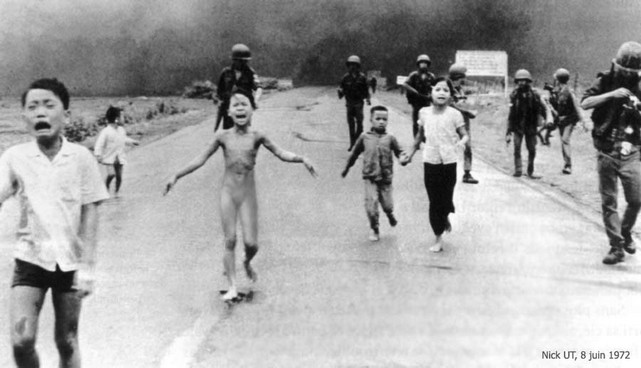

TRANG BANG by NICK UT

This seminal image from the Vietnam War by Nick Ut tells a well-known story: the horror of war; terrified children; anxious soldiers. Napalm has been dropped on the village Trang Bang, and the victims are being shepherded to safety—yet when we change the frame, the story changes too. Below you see the real-life banality the picture editor left out. Pictures tell stories. Series of pictures have the power to convey narrative.

THE MOVING IMAGE

If a photograph occupies two-dimensional space, a movie is the still image’s three-dimensional counterpart. The allure of a captured moment is stretched to a series of images—a narrative that develops through the added dimension of time. Photography is truth. Cinema is truth twenty-four times per second (Jean-Luc Goddard). By this measure, film sequences should easily defeat still images in the business of storytelling, yet it is plain they don’t consistently succeed. The extra dimension is not just a landscape to explore, but one within which to get lost.

If we add time as a valid dimension to our two-dimensional frame, we still have only three dimensions to the real world's four. If we now move that frame through space, we come closer to the 'moving perspective in a changing world' mentioned in the introduction. In the two-dimensional image below, we perceive depth. If we run time, the perception is not necessarily amplified—only when the frame moves, does depth leap into reality. First scan the image for depth clues, then play the clip.

We have great reasons for wishing to move the camera. The freedom to range in this extra dimension is exhilarating. We may wish to follow the action, to establish a narrative element, or even just look at something different. The narrative possibilities for the camera exploring the 'seamless storytelling continuum' appear endless, yet watching one hour of MTV shows that this is not the cause for celebration it might appear to be. In The Library of Babel (a short story by Luis Borges), exists every possible book: every book that was ever written, every book that is ever to be written, every book that it is possible—ever—to write. This doesn’t mean that you can drop in and read the wisdom of eternity. This means that you can spend your entire life looking for just one book containing something other than pages of nonsense.

When the camera takes the narrative stance, and moves through the world it is capturing, it navigates a similar hyperspace of possibilities. We use every element possible to direct the audience's attention to where we want it, but each added element has the power not only to present, but to distract and confuse. Adding extra dimensions to storytelling increases, by orders of magnitude, the chance to go astray, breaking the narrative thread that viably connects one point to another.

STEADICAM

To look at how the thread gets broken, we'll examine pairs of sequences sufficiently similar to each other to bear comparison. The opening sequence of the space-western Serenity (Joss Whedon 2005), is two Steadicam shots joined by a edit hidden roughly in the middle. The motivation for the sequence is probably threefold: to introduce the protagonists in their various elements; to show the set in almost its entirety; and to make a long, exciting master shot to kick off the film.

The shot starts well, with simulated turbulence from the operator adding to the tension. That we linger on the wide two-shot, instead of cutting away to the view outside or to fingers punching the control panel, is at least a decision. Only when we move out of the cockpit to follow the captain down the companionway, and loose all but the top of his head—in order to hold the mercenary in shot—does the choice not to cut to a reverse-angle shot look dubious. Now the camera moves around them, crossing the line, with the mercenary first shrinking, then growing relative to the captain in a way that is inconsistent with the dialogue; but we are at least set up for a pretty good whip-pan and dutch angle. We explore more of the set, with another back-of-the-head shot going down the steps, and since we don't have another character to lock on to, we see the captain descend first, and then the camera descending. Had the operator boomed down in tandem with the subject, we would not have lost contact to the same extent. As it is, it feels a little like a POV—as if a new character is following. The over-the shoulder-sequence with the engineer works well, even though she slips into frame a fraction late for the move, and the switching two-shots with the doctor certainly helps along their turbid exchange. Notice how the relative sizes of the two actors in frame concords with the dialogue. It's good work.

We pan off to follow the captain, and now comes an inexplicable whip pan—inexplicable except that this is the hidden edit.* To quote Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown, Nobody ever walked out of the theatre because there was an edit. Which is better, a well-considered edit that advances the storyline, or a clumsy move that lengthens a shot? We stray into the realm of personal taste here, but I'm reaching for the razor. What is so compelling about a continuous shot, that you would throw in an incongruous move just to hide an edit? The shot recovers somewhat, with the camera taking its cue from the movements and gestures of the actors; but from here to the end of the clip, we are just following people around, and by the time it's over, we realise that it was all a device to introduce the set and the protagonists. The opening titles come as a relief.

Contrast this with the 'Grand Central Terminal' shot from the gangster movie Carlito's Way (Brian De Palma 1993).

Both shots succeed in matching action with camera movement, and at advancing the narrative, but Carlito's Way excels due to exceptional motivation, meticulous planning, and professional excellence. Even though the shot is more complicated than the one in Serenity, there is no moment of discomfort at any point, and no sensation of the camera's presence disconnected from the action. When we cruise over Carlito's shoulder to look down on the concourse, we slip into his POV, but then whip-pan effortlessly back into a reverse-angle. The camera move overrunning Carlito at the top of the escalator—and continuing down on its own—is radical, yet it works. In Serenity, we didn't notice the cleverly-hidden edit. In the Carlito's Way clip, we don't care about the edit; even though, two thirds of the way through, we cut away to the big guy puffing up the steps, before cutting back into the same take on the escalator again—and nobody walked out of the theatre. Even though Larry McConkey's operating throughout is peerless, there is no resistance to editing it like any other footage.

*The spaceship was comprised of two different sets.

HAND-HELD

Now consider two clips from Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón 2006), a dystopian fantasy set in the near future. Although the cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki, wanted to shoot the bulk of the film on Steadicam, the director opted for mostly hand-held.

The first clip bristles with excitement. Though registering the surroundings, such as the refugees cowering in the bus, the shot never degenerates into pseudo-POV, thanks to the masterful synchronicity of the operator with his subject. The quality of the work is outstandingly reactive, taking its impetus directly from the narrative driving force—and the dash across the street is sensational in this respect.* Now watch the opening sequence from the same film.

The shot begins with a powerful, above-eye-line perspective tilted down to fill the frame with concerned faces. We move off now, sinking below eye level to hold the TV screen top of frame, but we hold it to the point of diminishing the protagonist as he exits the café. Now we loose him entirely as the camera pauses to scan the beautifully-dressed set. We catch him up now and wheel around, so as to be well-placed for the explosion. The shot must have been exciting to choreograph, but it feels contrived—and now the camera barrels along, waving from side to side in a way that draws attention to its presence. What is the language of the shot? It begins like an omniscient storytelling perspective, gliding over the counter, and it's certainly omniscient in that it knows where to be when the bomb goes off. In between, it seems awestruck and a little lost, until finally comes the uncomfortable POV.

Hand-held camera does not approximate how the human eye sees. When we walk down the street, the world does not shake so. The director perhaps wanted to impart a 'documentary feel,' but this is hard to reconcile with gliding through the counter, and anticipating the explosion. This might be one of the moments the cinematographer would have used Steadicam, but it's hard to guess why it wasn't shot as a series of reverse-angle shots cut together as a sequence. The uncertainty of the camera work almost prepares us for the explosion, which might have remained more of a surprise with judicious editing of tripod work. One point in the shot's favour, is that by making it one move, we might experience the feeling of our having just been in the now gutted café—but even this is ambiguous. The magic of moving the frame through space is sometimes just too compelling.

* The blood spatter on the lens was unintentional, and had to be digitally removed from the remainder of the shot.

DOLLY

There follow two dolly shots from consecutive films by Andrei Tarkovsky. First, part of the famous opening from the 1986 film Offret (The Sacrifice). A long tracking shot follows three characters from the lakeshore towards the nearby house.

Eighteen seconds into the clip, the camera moves on cue with the lead character, as he makes towards the house. Five seconds later, he stops, but the camera moves inexorably on. A few seconds later, the child crosses in the same direction as the camera move, the two other characters join him, and the shot feels back on track. But now there is the uncomfortable feeling of a frame moving with its own agenda that the actors had better keep up with—like a train leaving the station. Only towards the end of the clip, does the camera become reactive again to accommodate the postman settling himself in the grass.

We go back now to Tarkovsky's previous film, Nostalghia (1983). A tracking shot by the superb operator, Giuseppe Di Biasi, has a distinct feel, being neither anticipatory nor assertive, but wholly reactive to its subject.

When we move the camera, it becomes an active agent in the world, but how that movement transfers to the audience is determined by its narrative stance. In Sacrifice, the camera takes an almost protagonistic role in leading the scene to its destination. In Nostalghia, it is locked in step with the action.

CONCLUSION

In representing the moving perspective in a changing world, there are few rules that shouldn't be broken with impunity; but from the extravagant crane moves of Touch of Evil, through the radical perspective shifts of Carlito's Way, the explosive energy of the battle clip from Children of Men, to the subtle dolly work of Nostalghia, there is one common element: a rationale for camera movement that is entirely internal to the narrative.

The other moving clips suffer—to greater and lesser extents—from reference to a reality external to their narrative context. It is not enough to want to show a set, introduce some characters, or to make a long move in itself. In dramatic sequences, motivation for camera movement must be generated from within the narrative continuum. Movement without internal motivation is not just distraction: it is a failure of the imagination. For those of us lucky enough to be entrusted with this most powerful of storytelling devices—the moving frame—this presents an exciting challenge.